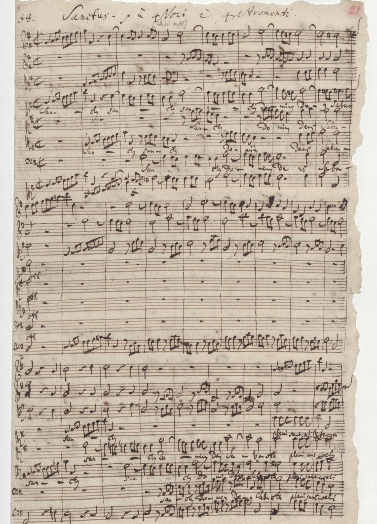

The soprano voice of the choir opens the vision of the saint with great ease with an upward-swinging gesture, the G major scale. This is immediately followed by a simple, rhythmic, contrapuntal counter-motif. The tenor canonically imitates these memorable motif gestures and the entire choir follows with contrapuntal motif realisations.

In a short interlude, the orchestra mirrors the choir in milder tonal colours. The first oboe and first violins begin with the soaring scale motif on the dominant, while the first and second oboes and violins then sing out the counter-motif broadly.

The choral choir then starts again with the soaring opening motif, harmonically varied in a sophisticated way, the other choral voices respond and the oboes play their counterpoint motif. Moved, the choral voices lead imperceptibly to the ‘Pleni-sunt-coeli’ and end in a final cadenza on ‘gloria ejus’ in E major. Under the leadership of the oboes, contemplation returns in a short orchestral interlude.

However, the alto and bass voices immediately recall the constant soaring of the seraphine and open up a kind of canonical narrowing of the musical motifs and, in the spirit of the vision of Isaiah, musically depict how some call out their holiness to others. The choir then turns more and more to the ‘Pleni sunt coeli et terra’, i.e. the pan-en-theistic view that God's splendour - ‘gloria eius’ - is recognisable in everything. The initial Sanctus motif withdraws more and more into the orchestra and disappears completely at the end in the joint D major jubilation of the orchestra and choir.

Bach probably added this festive ‘angel's song’ to the Leipzig Protestant liturgy at Christmas services. The fact that this Sanctus was later included in the Bach catalogue of works means that this festive work can still be performed today. In any case, Bach found this work perfectly suitable for use in church services and definitely worth performing in its revised form.