Franz Liszt: Andante lagrimoso and Cantique d’amour, from Harmonies poétiques et religieuses (1853)

Franz Liszt

Born 22 October 1811 in Raiding, Austrian Empire

Died 31 July 1886 in Bayreuth

Composition:

1833: First version in Paris: Harmonies poétiques et religieuses

1849–53: Conception and composition in Weimar of the edited version of Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, published in 1953

At barely 17 years of age, Liszt found himself in the midst of a profound personal crisis. His father had died in 1827, and he was unhappy because he was in love with someone outside his social class. Thanks to his great success as a young pianist, he was adored, but also exhausted. In addition, the world was in political turmoil; these were the politically turbulent years in Paris before 1848.

Liszt increasingly wondered whether it was not the task of art and religion to exert a positive influence on a society in crisis. Liszt read Byron, Chateaubriand, Lamartine and Lamennais, and was interested in the teachings of the Saint-Simonists and the social question. He temporarily withdrew from public life and even wanted to become a priest. In 1833, he composed the first version of Harmonies poétiques et religieuses – inspired by Alphonse de Lamartine's religious and lyrical poetry collection of the same name – a compositionally daring work that could not be performed in the Paris salons at the time. In the same year, 1833, Liszt met Marie d'Agoult and fell in love with her. She was unhappily married to the Count d'Agoult, who was 15 years her senior, and fled with Liszt to Geneva in Switzerland. This was followed by years of successful concert performances and triumphs for Liszt. After his unhappy separation from Marie, his new relationship with the Ukrainian Countess Carolyn von Sayn-Wittgenstein, who was also unhappily married, eventually led him to Weimar, where he found employment as court composer in 1848. It was only here that Liszt decided to review and redesign his piano cycle, which he had begun in 1833.

Between 1849 and 1853, Liszt completed Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, a cycle of piano pieces based on poems by Lamartine and texts from the Catholic liturgy. As musicologists are increasingly pointing out today, the entire cycle has a spiritual dramaturgy that is intended to lead to a religiously relivable transformation from suffering to joy.

Liszt adopted the preface that Lamartine placed at the beginning of his poetry cycles for his piano cycle in order to express what art, poetry and, indeed, his music might achieve in the Romantic self-image:

"There are contemplative souls who, in quiet solitude and contemplation, feel irresistibly drawn to supernatural ideas, to religion. Every thought becomes enthusiasm and prayer for them, and their whole being and life is a silent hymn to the deity and to hope. In themselves and in the surrounding creation, they seek steps to ascend to God; words and images to reveal him to themselves and themselves to him. May I have succeeded in offering them something of this kind in these harmonies!

There are hearts that, broken by pain, trampled by the world, flee into the world of their thoughts, into the solitude of their souls, to weep, to wait or to worship. May they gladly be visited by a muse who is lonely, like them; may they find harmony and accord in her tones, and sometimes exclaim in her song: We pray with your words, we weep with your tears, we implore with your songs."

Alphonse de Lamartine – from the preface to the ‘Harmonies poétiques et religieuses’

The entire cycle lasts around 90 minutes. Here we will limit ourselves to the last two religious-poetic mood pieces, the Andante lagrimoso and the Cantique d'amour. May this concentration lead you to listen to the entire cycle later on. For Liszt was much more than a piano virtuoso as an artist. The Harmonies are dedicated to Caroline von Sayn-Wittgenstein.

Listen here:

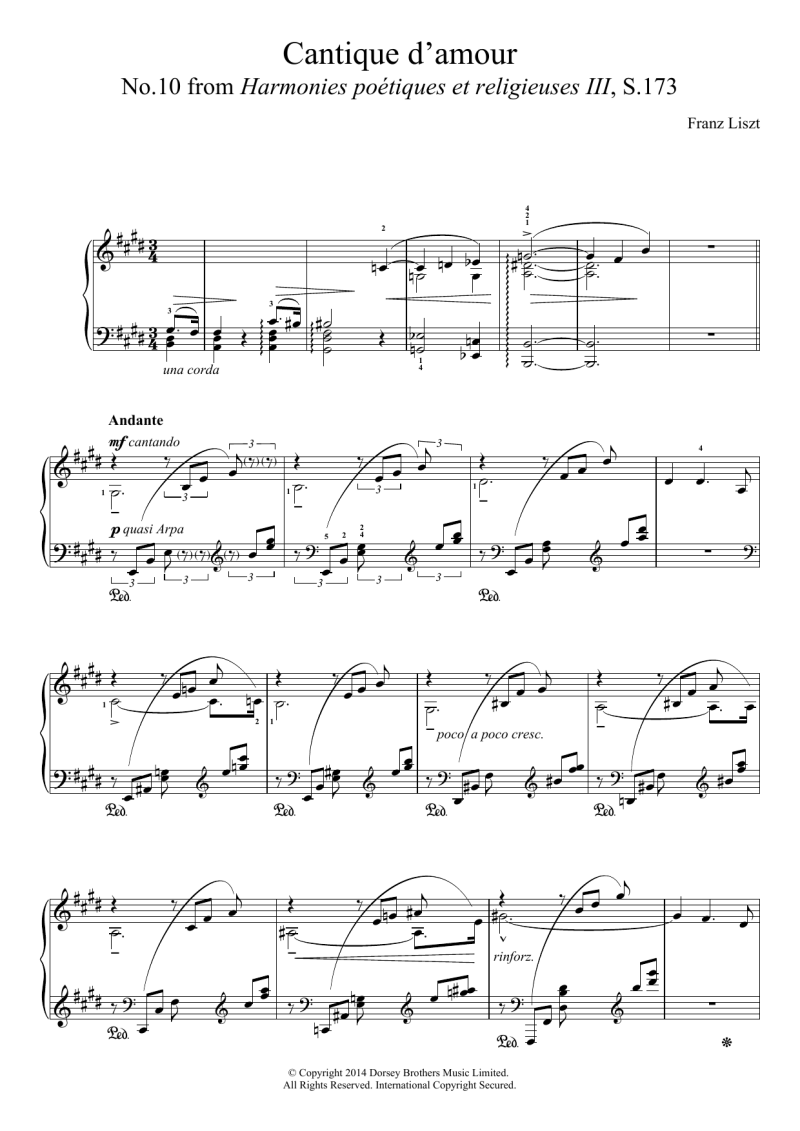

Andante lagrimoso (approx. 7 ½ min)

Cantique d’amour (approx. 7 ¼ min)