Arvo Pärt: Credo for piano, mixed choir and orchestra (1968)

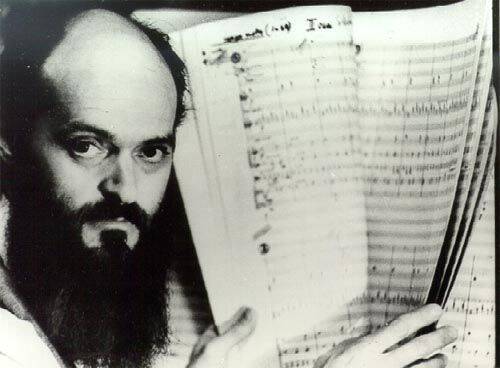

Arvo Pärt

born 11 September 1935 in Paide, Estonia

Premiere of Credo:

16 November 1968 in Tallinn, conducted by Neeme Järvi

Recordings:

1992 Philharmonic Orchestra, Boris Berman (piano), Neeme Järvi

2003 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hélène Grimaud (piano), Esa-Pekka Salonen

2025 Estonian Festival Orchestra, Kalle Randalu (piano), Paavo Järvi

In 1968, a work called Credo received thunderous applause from audiences in the former Soviet republic of Estonia and had to be repeated immediately. Newspaper reviews at the time were also positive, without referring to the religious lyrics. They reported ‘astonishing contrasts between contemplation and infernal orgies’. Arvo Pärt, composer of ‘Credo’, ‘uses long dynamic crescendos that electrify the atmosphere’. This music is seen as representing the ‘struggle and victory of order over chaos’. It is said to be the ‘most evocative’ of his collage works to date and made a great impression on audiences and critics alike. The conductor of the premiere in 1968 was Neeme Järvi, who had championed the work. However, the Communist Party and the official composers' association did not like the aleatoric, atonal style and, above all, the use of a religious text, and the work was not performed again for a long time. Pärt was sidelined in the official music scene in Soviet Estonia and even fell into a creative crisis. After Credo, he developed a new compositional style influenced by church music, which he called tintinnabuli (derived from the Latin for ‘little bells’) and whose first successes were his works Tabula rasa and Fratres. These works were very well received in the West thanks to violinist Gidon Kremer, EMC Music Publishers and Universal Edition. A whole new esoteric reception of Pärt emerged, which ignored his earlier works. Musicologist Oliver Kautny concludes that the enormous impact of Pärt's work in Soviet Estonia had little significance in the West. ‘Pärt as the “Stravinsky of Estonia” can only be understood in the context of Soviet conditions, just as the media myth of Pärt-Palestrina appears to be a belated romantic-religious phenomenon of a typically Western secularised society.’ It therefore seems that the context of reception in music, as in religion, is a decisive factor in the form of music or religion. Pärt's multifaceted work – like the pluralism of Christianity (!) – would probably have to be rediscovered in terms of hermeneutics of reception.

Credo thus offers an opportunity to hear Pärt's early work, which concluded with Credo, in a new light: a collage of diverse musical styles in which the C major tonality is deconstructed through atonality and ultimately returns to tonality via chaos, wild aleatoricism and simple improvisation. To this end, Pärt uses religious texts: first the purely confessional ‘Credo in Jesum Christum’, which is then concretised with a dictum from the Sermon on the Mount by the Jew Jesus, calling for a new universal attitude in practice: ‘You have heard that it was said, 'An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But I say to you, do not resist evil’ (Matthew 5:38). The credo at the end then refers to a non-violent, humanistic basis for action in society.

Listen here (12 1/2 minutes)!