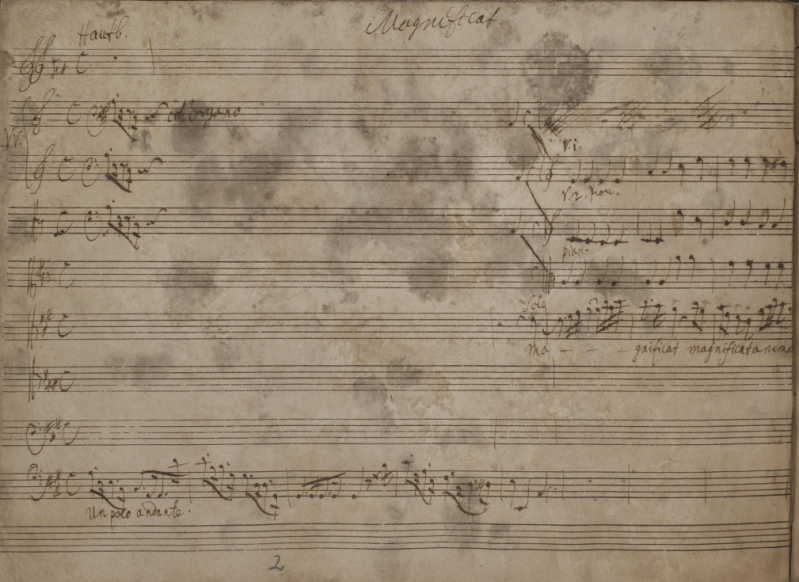

A descending, dotted unison from above focuses attention on the expression of Mary's inner joy. This is how one of the few settings of the Magnificat begins, with Mary singing at the start rather than a choir. The joy of the alto solo is expressed not loudly, but in a completely internalised melody. The voice rises gently, expands at ‘anima mea’ and descends in wonder at ‘Dominum’.

The melody begins anew three times (and is composed by Heinichen in an extremely differentiated manner), ending with a final joyful coloratura on ‘Dominum’.

Only then does the choir join in at a new tempo (allegro joyful), carrying the jubilation – in four parts – outwards and outdoing itself in constant polyphonic crescendos until the homophonic joint conclusion: to God our Saviour.

A lively syncopated melody played by the strings introduces a soprano solo. The melody of the aria conveys modesty and gratitude for an extraordinary destiny that spans generations.

Two transverse flutes create a new soundscape and prepare for a tenor aria. The tenor sings expressive melismas of grandeur, power and transcendence. At the same time, it is a reference to a sacred, awe-inspiring reality.

Fast eighth notes and repeating triplets form a memorable, powerful motif that is introduced by the orchestra and then taken up by the polyphonic choir in a canon that is highly effective. With this powerful performance, the proud are told of their insignificance and the powerful of their downfall in a series of mounting attempts. The triplets fall silent for a moment as God turns to the humble.

Two solo voices turn sensitively to the “Esurientes”, only to send the rich away empty-handed once again with the triplet motif and a powerful conclusion to “inanes”.

An expressive dialogue develops between the strings and flutes, into which the alto voice recalls God's choice and special commission to Israel to help build a better world according to God's will. The dialogue between the strings and flutes accompanying the singing becomes, as it were, a musical symbol of this cooperation between humans and God.

Since in liturgy – even in Heinichen's time in Dresden – the Magnificat is sung at the end of Vespers, it is followed, as after a psalm in liturgy, by a solemn ‘Gloria patri...’. The musical conclusion is a fugal ‘Sicut erat...’ in recitative simplicity but with an impressive, jubilant final effect.